有一支番鬼佬大戲裏面的主題曲,是用法文唱的。出於 Donizetti 的 “La Fille Du Regiment” (中英文翻譯分別是”連隊的女兒”和”Daughter of the Regiment”)。主題曲叫”Ah Mes Amis”,要求男高音唱出九個 high C,被視為對男高音歌唱家極具挑戰的一首歌。

我在思考金融問題時,習慣聽著歌劇。這首有九個 high C 的主題曲,給予我靈感,在金融領域上也想出九個 high C。這是九個值得金融持份者高度關注的 C,分別是:Conflict, Compensation, Competition, Complexity, Conduct, Compliance, Cost, Crisis 和 Culture。

很榮幸被邀在中大 Alumni Association of Surgeons 舉辦的”李國章傑出講座”演講。我利用這個機會,將這九個我認為值得高度關注的 C,寫進演詞內。在這裡也和大家分享。抱歉只有英文本。

任志剛

2017年10日13日

ARTHUR LI DISTINGUISHED LECTURE

Alumni Association of Surgeons

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

The Nine High Cs in Finance

Joseph Yam

13 October 2017

I have a habit, a good one I think; and this is to do what doctors tell me to do. So when Uncle Arthur asked me to speak at this function I did not hesitate and agreed. I was at a loss afterwards as to what I, as some kind of a finance person, can meaningfully share with a group of surgeons. The only thing, I think, I have in common with surgeons is that I am also quite skillful in doing things with my hands. But I did not have the courage, like you, to handle life with my bare hands, so I chose to do woodwork instead as a hobby. Let me show you one of my works: two interlocking endless chains craved from one block of wood, with no stitches, no bandages, no glue and no tricks involved [Note 1].

Yes, I have much respect for doctors, surgeons in particular. Let me tell you this story about two classmates: one became an investment banker on Wall Street and the other a surgeon. At a class reunion, the investment banker was keen to boost how successful he had been, of course in terms of how much money he made: something like US$20 million in the past year. Looking at this surgeon classmate of his condescendingly he asked: “what did you make”? The surgeon, calmly and confidently, answered: “I made a difference”.

But to be fair to the investment banker, and indeed to the many of those working in the finance industry, they do have an important role to play in society. Whether or not they play this important role well is another matter. Generally speaking, there are two types of people or entities in society: those with money wishing to seek a return for it and those without money wishing to raise it so that they can deploy it for whatever they want to do – to finance different types of businesses, to buy a home or a clinic, etc. Obviously, if money can be safely and efficiently mobilized from the former to the latter, rather than being kept under mattresses, the public interest will be well served, in that the economy will then prosper.

But there is understandably a mismatch between the risk appetites of those with money to invest and the risk profiles of those raising money. This principally is because of the lack of information, time and the necessary skills to identify, quantify and manage risks. For example, with so much time spent in the operating theatre, you, as an investor, would probably not be in a position objectively to assess the credit-worthiness of even a close relative who needs money to buy a home, to the extent of feeling comfortable in lending him money directly. So we need financial intermediaries of different types, collectively forming the financial system, to do the matching of risk appetites and risk profiles, and in the process to mobilize money in support of the economy. Specialized skills are required to perform this matching, which basically involves:

• The transformation of risks – as in the case of banking where the credit risks of borrowers are transformed into the credit risks of banks which, with prudential supervision by the banking regulator, depositors generally accept;

• The transfer of risks – as in the case of the securitization of mortgages (or other risk assets on the books of banks) and the distribution of these securities to investors; and

• The transaction of risks – as in the case of market-making of financial instruments to provide liquidity and reliable price discovery, so as to attract investors’ interests in them.

Has the financial system performed this conceptually simple task in the mobilization of money well? Given the recurrence of debilitating financial crises of an international dimension, the answer, I am afraid, must be “NO”. Then, the next questions on everybody’s mind must be “what went wrong?” and “how do we fix it?”

Yes, I will at least try and address these complex questions tonight. But let me first share with you another hobby of mine – listening to operas, and in particular, the feature arias that define those operas for me, like “Nessun Dorma” in Puccini’s “Turandot” or “Celeste Aida” in Verdi’s “Aida”. Opera music is essential for me when thinking through problems in finance, just like some of you listening to it at the operating table. One of my favorite arias is “Ah Mes Amis” in Donizetti’s “Daughter of the Regiment”, which is famous for the nine demanding high Cs for Tonio the leading tenor role. Being king of the high Cs, Pavarotti of course delivered them extremely well, notably at Covent Garden in 1967 or in the Metropolitan Opera House in 1972, when his voice was simply pure (but also a little clinical to me). I think only Juan Diego Florez matched his excellence in delivering this aria in 2007 in Vienna. Florez sang the nine high Cs with such force, control and comfort that it stopped the show for nearly ten minutes, with thundering applause from the audience [Note 2]. This was just before the global financial crisis broke, with much fire and fury, and inflicting much pain on the world economy. That aria prompted me later to identify also nine high Cs in finance that are much less pleasant – nine highly problematic Cs that I wish to share with you this evening.

The first C stands for CONFLICT. This conflict is a fundamental one, between the public interest in finance on the one hand and the private interest of the financial intermediaries on the other. The public interest in finance, if I may attempt to articulate it, is one of ensuring that the financial system efficiently serves the users of financial services, which then promotes the general economic wellbeing of society. The private interest of the financial intermediaries is obviously the maximization of institutional profit and individual remuneration, and providing themselves with all sorts of benefits in kind, for example, their palatial working environment, lavish entertainment and travelling in style. The conflict can be readily appreciated by considering the financial intermediaries as the middle man between investors and fund raisers, matching their risk appetites and risk profiles, as I mentioned earlier. The more successful is the middle man in extracting gain in the process, the worse deal the users of financial services get, in terms of a lower rate of return for their money and a higher cost of raising money. The users of financial services pay for the cost of financial intermediation. The higher the cost of financial intermediation, the lower is the efficiency of the financial system.

There is of course conflict almost everywhere in society. It is for the responsible authorities suitably to protect and promote the public interest, if there is identified a need to do so, and strike the right balance. This is a political process and the outcome reflects the interaction of political power between the stake holders. The users of financial services are collectively politically passive. The majority just want the loan that they badly need and the safety of their deposits. They are not in a position to bargain. By contrast, being in the position of controlling where money comes from and where it goes to in the economy, the financial intermediaries typically have much political clout. They are quite skillful in wielding those political influence to promote their interests, including keeping the regulators at bay. Look at Wall Street and its extensive presence in the White House and you can appreciate how influential they are. Consequently, the resulting balance between this fundamental conflict between the public interest of promoting financial efficiency and the private interest in the maximization of profits and remuneration by the financial intermediaries is very much tilted in favour of the latter. In my opinion, it is an unfair balance, perhaps disgustingly so.

This conveniently takes me to the second C, which stands for COMPENSATION. The investment banker I mentioned earlier, who made US$20 million in a year, happens to be just a trader. He has probably been successful in generating substantial revenue for his investment bank and was given a sizable bonus. In his mandate as a trader, there is much emphasis on revenue generation and he is remunerated principally on this quantitative performance measure, although there are other measures relating to the quality of risk management, compliance and conduct. Higher up through to the top management of an investment bank, compensation also has a clear and prominent linkage to different measures of revenue or profitability. A common practice is for there to be a bonus pool into which a substantial proportion of revenue is routinely transferred during the year. And when the investment bank scores a big deal, there would be a special transfer. All this typically meant that variable compensation in an investment bank amounts to about half of profits before tax.

You probably know how much a CEO of an investment bank on Wall Street make. I don’t even want to mention it. But I am not jealous of it. I just wonder sometimes what exactly are the professional skills and personal qualities that put someone in such an “enviable” position. I can understand why, in the medical profession in Hong Kong, there is an abundance of what is now called “man from the planets” (星球人) or “man from the moon” (月球人), and I am happy for them because most of them don’t sleep saving lives and taking care of our health. But taking advantage of being in a privileged position, protected by licences, to determine where money comes and goes in the economy to extract astronomical compensation is another matter altogether. And to realize that this is at the expense of the users of financial services makes it worse. Thankfully, the use of huge amounts of public money to bail out banks which were regarded as too big to fail in the developed markets in the 2008 crisis has drawn attention of the financial authorities to the possible need to regulate compensation practices, if not compensation levels, and there are regulatory initiatives on the table. Whether this effort can be sustained or is effective in curbing compensation, thus leaving more with the users of financial services, is still to be seen. My view is that there is a need for a more fundamental change in approach, which is for compensation to be determined by how well the users of financial services are being served.

Let me move on to the third C, which stands for COMPETITION. Finance is a captive industry in which financial intermediaries have to be licensed or registered by the financial authorities, and subject to prudential supervision and conduct regulation, for the good reason, among other things, that the users of financial services, especially the small investors and depositors, need suitable protection. There are, for banks, the usual capital adequacy requirements, liquidity requirements and leverage restrictions to limit risk-taking. Apart from these, most financial authorities adopt a market-based approach to finance, allowing the financial intermediaries to identify, take, price and manage risks associated with their businesses. Against this background, the licensed financial intermediaries compete freely for business.

This is fine, at least for the bread and butter type of banking business of taking deposits and extending loans. Competition largely takes the form of price competition, resulting in higher deposit rates for depositors and lower borrowing rates for borrowers, compared with the case when an interest rate cartel was still considered necessary to prevent cut throat competition. I am glad that I managed to get rid of the Interest Rate Rules of the Hong Kong Association of Banks back in the nineties. We now have a net interest margin (NIM) in Hong Kong that is significantly lower than in other jurisdictions – a measure of financial efficiency that we can justifiably be proud of [Note 3]. This is absolutely in the public interest, although not in the private interest of the banks.

However, in other areas of this money business where there is less uniformity in the delivery of service, competition also takes other different forms of a non-price nature. The majority of users of financial services are not in a position to make meaningful comparisons before they make a choice. Sometimes there simply is not enough information disclosed to make a rational decision on the services and financial products offered to investors. As a result, the balance of interests shifts in favour of the financial intermediaries against the users of financial services. Indeed, different business models are designed for the principal purpose of bringing in more revenue and therefore enriching the bonus pool rather than better serving customers. This is notwithstanding the regulatory requirements on capital, liquidity and leverage, which somehow the financial intermediaries cleverly manage to get around or to minimize their restrictive impact.

One manifestation of this type of non-price competition is the move towards COMPLEXITY, and this is my fourth highly problematic C in finance. There are probably now more people trained as rocket scientists employed in the finance industry than in building rockets! They are engaged to design complex business models, making use of advanced information technology, to beat their competitors and other players in the typical zero-sum games of trading in financial markets [Note 4]. My view is that to win a zero-sum game, you need to possess at least one of three attributes: luck, skill and inside information. Luck is something that you cannot count on forever; skills can be replicated quickly as there are more than one rocket scientists and even the best ones have a price; and the use of inside information is cheating, unethical and possibly illegal. You simply cannot play a zero-sum game and expect to win on a sustainable basis. The use of inside information is however a grey area in terms of defining insider trading, outlawing, effectively policing and proving it [Note 5]. This regrettably puts those with privileged access to such “professional” financial markets as the foreign exchange market and most over-the-counter markets for financial derivatives at a distinct advantage. They know the collective desire of the customers they are supposed to serve. They would go as far as to engage in front-running, arguing that they are merely “pre-positioning” themselves so as to serve better their customers. In practice, this becomes the source of billions and billions of trading profits of the investment banks that you hear reported regularly. Perhaps you will be happy if you are a shareholder of those investment banks, but who then are the losers of this zero-sum game? They are the poor users of financial services!

Complexity extends from business models to financial products offered to investors. The aim, it is claimed, is to maximize return for their customers, making available to them a significantly higher yield for their money than those that can be derived from the traditional financial products like deposits, bonds and equities, for example, the triple-A rated minibonds issued by Lehman Brothers yielding 6%, compared with less than 1% for bank deposits. First order derivative products with a high degree of leverage betting on the changes in the prices of certain financial products, stock index futures and warrants for example, have become quite common. Then there are the more exotic structured products that involve pooling different types of financial instruments, including derivatives, and slicing them into different tranches of varying risk ratings assigned by rating agencies to enhance their attractiveness. In a low interest rate environment with investors keen to search for yield, these complex financial products proliferated and are given simple acronyms that give them misleading legitimacy: ABS, BBC, SIF, MBS, ABCP, CDS, CDO, CLO, etc., etc. They are like a big bowl of thick alphabet soup. You can’t possibly see the bottom of it, in other words, you can’t see clearly the risks involved. Because you are hungry, you take it anyway, urged on by the experts wanting your business; and by the time you see the bottom of the bowl, you probably have had too much of it already. And the consequence is not just indigestion. Some of the combination of alphabets may have become toxic.

In some investment banks, the business to “originate and distribute” complex financial products is like running a production line in a factory. Origination involves the process of acquiring different financial assets, mixing, slicing and packaging them into deceptively simple structured products. Distribution involves either marketing them directly at retail outlets or pushing them to investors through private banking and wealth management operations. Because the demand is there, this business is highly profitable, in terms of fees for running the production line and trading profits from market-making and position-taking. There is therefore management pressure for the production line to be run at a high speed. As a result, the quality of the input and the safety of the production line are compromised, and the output becomes potentially toxic, making it highly vulnerable to significant falls in the price of the input. This is exactly what happened in the US to the so called Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) using residential mortgages as the principal input. Pressure to keep the production line running at high speed led to the use of sub-prime mortgages of typically 100% loan-to-value ratios and the use of counterparties in the production process who are unable to deliver when under stress. You know what happened when the residential property market bubble in the US burst in 2008.

Let me move on to the fifth C – CONDUCT. This is again a highly problematic one. Incentive shapes conduct. Along with questionable business models at the institutional level is questionable conduct at the level of individuals. It is not difficult to appreciate the mentality of a trader in his late twenties or early thirties arriving at his trading desk. He is given a mandate that has much emphasis on revenue generation. He is remunerated largely, or in some cases solely, on how well he does in revenue generation in the form of variable pay, the amount of which pales his pitiful little amount of fixed pay in comparison. His next vacation, sports car, mortgage payment for his decent home and many other luxuries he craves depend on his performance at the desk. Yes, he is also given position limits to observe and under close surveillance. But the pressure is there; so is the temptation to walk over the line.

Problematic conduct takes different forms. Unauthorized trading is one; perhaps hoping that making big money for the firm while breaching limits or hiding the breaching of limits would be tolerated. Manipulating the fixing of benchmark prices, such as those for interbank money market rates and exchange rates, is another; perhaps hoping that such manipulation would help to show greater profits attributable to him or his team and choosing to ignore that the fundamental role of benchmarking is to facilitate accurate price discovery. Cheating customers on what the prevailing price is in markets to which the firm has privileged access is yet another; perhaps hoping to profit the additional few “pips” when the unknowing customers deal with the firm at marked-up prices, away from market prices that are considered to be fair even after including a reasonable “spread” to pay for the service. Let me quote what a trader said when testifying in court recently in a financial market manipulation case to underline the seriousness of misconduct in finance. He said: “I wanted every bit of money I could get because that’s your performance metric, that’s how you’re judged”. In another court case concerning manipulation in the foreign exchange market, tapes on conversations in the dealing room revealed an interesting statement by another star trader. He said: “if you are not cheating, then you are not trying hard enough.”

Let me move on to the sixth C – COMPLIANCE. This is something that bankers moan and groan about very much nowadays. I don’t blame them, particularly for those who are running the bread and butter businesses of taking deposits and extending loans, which is a rather basic mechanism in the mobilization of money in support of the economy. They are not the complex, cutting edge financial businesses typical of Wall Street. So when the problems originating in Wall Street led to regulators imposing intrusive requirements – very much shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted – and these requirements are implemented globally given the globalization of finance markets, there is every reason for the conservative and well-disciplined banks to feel unhappy. Indeed, regulatory compliance has become a heavy burden to the industry [Note 6]. In the dealing rooms of banks, no matter what you are doing, whether it is proprietary trading, asset management, serving clients in wealth management or private banking, all oral conversations are now taped. There are also elaborate computer systems and a large number of supervisory staff to monitor behavior, including analyzing the use of words in the millions of on-line conversations. There are posters to remind employees the need to behave. These remind me of the novel 1984 by George Orwell and the famous slogan therein that “Big Brother is Watching You”!

And Big Brother is getting bigger all the time. With information technology revolutionalizing the delivery of financial services, adding complexity and risks that have to be managed and monitored, the role of Big Brother has been expanding and becoming more sophisticated. Big Brother is also very expensive, adding much to the overall COST of doing business in finance, and this is the seventh C. Apart from the astronomical staff costs and compliance costs, there are the huge overheads. And there are the hefty fines that regulators and law enforcement agencies impose on banks as punishment against institutional misconduct and failure to prevent employee misconduct [Note 7]. The total cost of running the financial system is the cost of financial intermediation or the cost in the mobilization of money from those who have it to those in need. It is obviously paid for by the users of financial services, in the form of the difference between the rate of return for the money of those who have it and the cost of money for those raising it; in other words, the intermediation spread. In the simple case of traditional banking, the intermediation spread is the net interest margin (NIM) between the deposit and lending interest rates, from which the costs (including the profits) of running the bank are paid for.

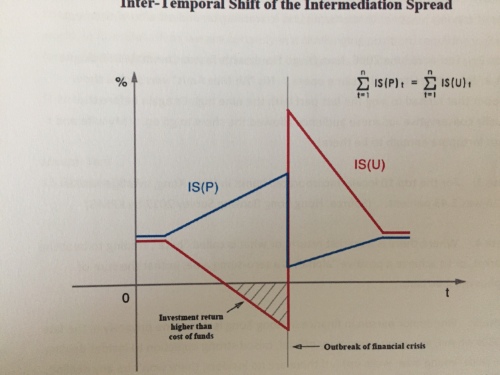

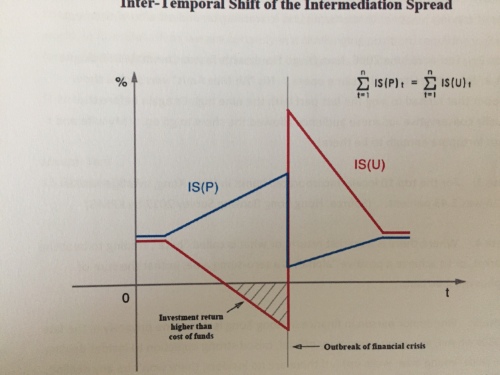

The intermediation spread, as measured by the cost of running the financial system, should be identical to the intermediation spread, as measured by the difference between the rate of return for investors and the cost of raising money by borrowers. However, we often observe the anomalous phenomenon when, on the one hand, investors enjoy a high rate of return for their money and fund raisers can borrow cheap money, in other words, a low intermediation spread from the point of view of the users of financial services; while, on the other hand, financial intermediaries concurrently run large overheads, make much profit and pay huge bonuses to their staff, suggesting a high intermediation spread from the point of view of the service providers. To explain this anomaly demands an academic thesis. But let me offer a simple explanation. This lies in the time dimension, which provides much room for manoeuvre by the financial intermediaries in running this lucrative money business. The mathematical identity between the intermediation spread from the users’ side and the intermediation spread from the service providers’ side holds true not every day, every month or every year, but over a period of time. The anomaly I described earlier involves a shift of the intermediation spread paid for by users of financial services from the future to the present into the pockets of the service providers! I call this an inter-temporal shift of the intermediation spread or, to use a convenient acronym, ISIS!

I have, in fact, moved onto the eighth C; and this C stands for CRISIS. To enrich compensation in a competitive environment, the financial intermediaries engage in questionable business models, go for complexity and their employees drift into misconduct in the delivery of services. In the process, unknown risks that are systemic in nature are created. Yes, for a while, all were happy: the investors, the fund raisers and, of course, the financial intermediaries themselves. But when the unknown systemic risks materialize, involving a collapse in the prices of financial assets and insolvency of financial institutions, in the form of a financial crisis, payback time comes. Investors suffer large losses, borrowers have to pay very high costs for raising money, if money is available at all. In other words, the intermediation spread paid by users of financial services widens sharply, wiping out the benefits of high investment gains and low cost of funds enjoyed in the past. A financial crisis is, in effect, a brutal and sudden manifestation of the inter-temporal shift of the intermediation spread that had occurred. ISIS has struck [Note 8]! This is perhaps why CRISIS is spelt with ISIS behind it. As to the financial intermediaries, losses are incurred, some to the extent of requiring bailouts by the authorities, using taxpayers’ money. At the management level of these financial intermediaries, however, the musical chair starts. The majority of them, having already pocketed fat bonuses in the “good” times, will still land fat jobs elsewhere. Thus I have developed this simple theory of mine for consideration by those with responsibility over the financial system: whenever you notice an anomaly between the two measurements of the intermediation spread, from the users’ side and the service providers’ side, an inter-temporal shift of the intermediation spread may be occurring, implying the possibility of a financial crisis looming.

The time dimension urges me now to move on quickly to the last of the nine highly problematic Cs in finance, some kind of a crescendo to sum it all. This C stands for CULTURE. Put simply, finance is a service industry that has sadly become self-serving. The industry abuses its privileged position protected by licences to determine where money comes from and where it goes to in the economy for its own benefit. It has enormous political clout in ensuring that the rules of the game in finance work in its favour. It energetically waves the attractive banner of the free market, seize the moral high ground and condemn intervention by the authorities. It puts the private interest of profit and bonus maximization over the public interest of ensuring financial integrity and efficiency. It goes for complexity and adopts business models that erode standards and create systemic risks. It is run on an incentive system that condones institutional malpractices and individual misconduct by employees to the disadvantage of users of financial services. It breeds financial crises that cause extreme hardship to users of financial services and hurt the economy. This self-serving culture is simply not in the public interest.

What then is the cure? If my diagnosis is correct, we need major surgery, not so much a cultural revolution, but certainly a fundamental change of culture from being self-serving to one that has an overriding emphasis on serving well the economy. This should involve a comprehensive review of the governance of the financial system, on the one hand, to put financial authorities in a position more proactively to promote and protect the public interest in finance, and on the other hand, to ensure that the financial intermediaries recognize clearly the purpose of their existence, behave and be remunerated accordingly. This, in effect, means going back to basics in finance. This means less complexity, less cutting edge finance that cut off the limbs of users of financial services, a lesser and less expensive role for Big Brother, lower cost for financial intermediation, greater financial efficiency and safety, and less regulation. Elsewhere I have articulated in a little more detail two recipes for financial culture reform, one for the financial authorities and one for the financial intermediaries. As I think you probably had enough of me this evening, I will leave those of you with an interest in the subject to find these in the website of the Institute of Global Economics and Finance at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Let me end, however, by saying that I am not hopeful that we will see quick changes in financial culture in the near future. This is a global problem that requires global efforts to resolve. The combination of capitalism and western democracy will limit progress on this front, if there is initiative to do anything at all. Donald Trump is surrounded by wise men from Wall Street. Soon we will see whether he will pick an additional one to be Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank. On Wall Street, which in reality is the source with the strongest influence on global financial culture, there is more talk on de-regulation than, for example, on the regulation of compensation practices in the industry. There is also talk about repealing rather than strengthening the Dodd-Frank Act, which was enacted as a response to the financial crisis of 2007-08 principally to prohibit proprietary trading by banks. But I am pleased that in the socialist, market economy up north, which is now the second largest in the world, there is in financial governance a strong emphasis in finance serving the economy. Perhaps that was one reason why the Mainland was never quite affected as badly by the two financial crises of the last two decades. For Hong Kong, as the international financial centre bridging the Mainland and the rest of the world, in financial affairs we are certainly in a challenging position, requiring vigilance, foresight, clarity of purpose, preparedness in response and decisiveness in action.

Thank you.

Joseph Yam

13 October 2017

Note 1: I used a block of fir, measuring 6x6x15 cm, I bought from Tokyu Hands in Osaka. Fir has fairly tight grains and it is not too hard; just the right texture for this type of craving. I spent three months on it, working on and off after retirement.

Note 2: Earlier in June 2006, Juan Diego Florez with Teatro Commale Di Bologna was in Tokyo to perform the same opera. His “Ah Mes Amis” was such a show stopper that he had to sing the last part with the nine high Cs again before the usually conservative Japanese audience allowed the show to go on. My wife and I were fortunate enough to be there!

Note 3: For the top 10 locally incorporated banks in Hong Kong, average NIM in 2016 was 1.43 percent. (Source: Hong Kong Banking Survey 2017 by KPMG)

Note 4: Where there is a market return, or what is called “beta”, trading to beat the market, or to achieve a positive “alpha”, is a zero-sum game, in that the sum of alphas must be zero.

Note 5: One senior person in finance in Hong Kong lectured me privately in the late 1980s when I, as a young monetary official, raised strong objection to insider dealing. He said: “young man, wake up! If there are no insiders, there won’t be any dealing at all and you will have no market!”

Note 6: One research firm recently put global spending among banks on compliance at almost US$100 billion in 2016, growing from 15% to 25% annually over the past four years.

Note 7: According to a study by the Boston Consulting Group, financial institutions have paid US$321 billion in fines related to the financial crisis of 2007-08.

Note 8:

IS(P) is the intermediation spread measured from the service providers’ side, which is the total cost, including profits, of having financial intermediaries performing financial intermediation.

IS(U) is the intermediation spread measured from the users side, which is the difference between the rate of return for investors and the cost of funds for fund raisers.